Norris Center Art-Science Residency Complete Projects 2022

Mapping Sonic Futurities

By Alex Wand, Published in Refract: An Open Access Visual Studies Journal, 2022

Mapping Sonic Futurities (MSF) combines sound art, listening practices, and ecological research to trace the present and future histories of ecological habitats. The project involves twenty-four-hour “sound vigils” in outdoor spaces and habitats with tenuous futures. During these retreats, the keeper of the vigil commits to being in one location for an entire day and night. For each of the twenty-four hours, they dedicate time to acts of ecologically engaged listening and sounding. This involves making field recordings of the space, performing music that responds to nearby sounds, and/or sitting in meditation with a focus on modes of listening outlined in a series of guided prompts. UCSC locations of sound vigils.

Wetlands

By Nena Hedrick

During the Norris Center Residency, I collaborated with Allison Payne of the Beltran lab to produce a work based on their research in acoustic monitoring of the deep ocean using elephant seals as sensing bodies. I accompanied Allison in the process of tagging the Elephant seals and relocating them while documenting the process on video. We started the process with the intention of creating an immersive installation connecting light and depth with the soundscape collected by the seals. Unfortunately, the seal and the data never came back. In the absence of a true record, the speculative might serve to create an imagined reality, future, present, or past. The speculative record of the non-human is anything but new. Taxidermy, as an art form, is the institutionally accepted “true” record of the physical existence of a being. Filling the skin (the original and true document) and posing of the figure are acts of forming a new non-human reality through a human context and interpretation. The taxidermist decides the enduring reality of the animal, leaving space for an imagined reality and a new interaction between these two beings. In line with this speculation based in absence, this work offers an interpretation of the sounds one might have expected from the elephant seal recordings. The soundscape is based on descriptions from Allison Payne and composed of audio available in the MBARI hydrophone archives which constantly acoustically monitors the Monterey Bay. Wetlands imagines a layered, abstracted experience of being in the deep ocean and being in the skin of the seal which determines its interaction with the space and light around it.

Wetlands Norris Residency 2022 (audio & video)

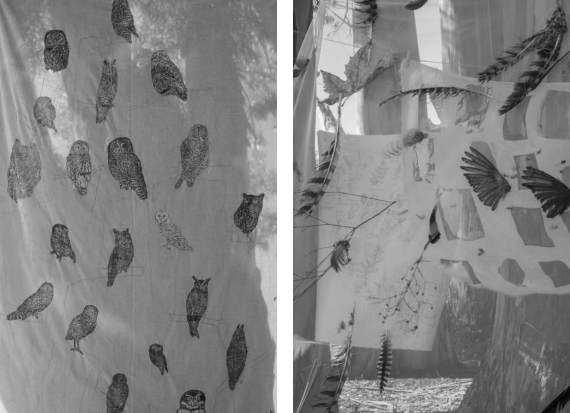

Owls of North America, Unwoven

By Grace Brieger

Owls of North America, Unwoven is a multimedia installation that portrays the artist's deep connection to the natural world and avian creatures. Through printmaking, poetry, fiber-work, and illustrations, the work seeks to bring an audience into the intimate lives and spatiality of twenty-one different owl species living across North America. Heavily connected to a book which the artist made during the height of COVID-19 pandemic, the installation serves to deconstruct traditional forms of printmaking and set the owls free. Nameless, placeless, they hang from eucalyptus bark and sway with the wind, as if to be one entity united by the resources that surround them and the forces of humankind, which often seeks to draw borders across spaces and deforest critical habitat. Owls teach us the importance of solitude and quiet pondering; different from a long informative song of a grosbeak, or the tune of a hermit thrush, the owl speaks a soft message to those who are willing to hear and respond. Being connected to different ecologies of California, the importance in the chatter and in the quiet has made itself known. There is time to sing like a songbird in the light of day and time to reflect along the quiet night, like an owl. There’s time to dance, laugh, and cry; there is time to release your breath into the traveling wind and wait patiently on the night's edge. This installation serves as an embodiment of the teachings of owls, but is also the artist's way of expressing her deep gratitude and respect for these creatures of the night. There are many elements at work, from a map of the most common plant species, woodblock prints of owls, and a wind-trap of resources and organic objects. By setting up the installation in an owls home which the artist has been visiting for many years, this work pushes art-science communication by weaving the owls of the eucalyptus grove into the dialogue. Though the artist feels the work belongs best in an outdoor setting, she hopes to display the work in a controlled space for more to see at a later date.

Dung beetle night shadows

By Amelia McKee

I created three dung beetle models inspired by entomological shadowboxes in collaboration with researcher Suzanne Lipton, of the Philpott lab concerning her research on the effects of grazing and landscape management on dung beetle communities and the subsequent effects on the soil microbial community and soil organic carbon content. Models of three of the most common species of dung beetles that Lipton encountered in her research were created to illustrate the diversity of the dung beetle community. These scaled paper craft models were made using cardstock, glue, acrylic paint, and varnish. Each species is mounted on a background related to an aspect of its ecosystem and life history.

The Onthophagus taurus model is mounted on an acrylic painting of a prairie supplemented with hay from one of the research field sites, because Lipton’s specimens were collected from cattle-grazed coastal prairies. The Aphodius fimetarius model is mounted on a soil backing created with collected soil from a field site; the soil represents their role in nutrient cycling, as well as their possible effects on microbial communities and soil organic carbon content. Lastly the Aphodius haemorrhoidalis is mounted on an acrylic painting of the Milky Way galaxy as previous research indicated that some dung beetles orient at night using the Milky Way. These backgrounds contextualize the lives of dung beetles and provide insight into their ecological roles as well as their part in ongoing research.

Urban gardening within the Santa Cruz Oaxacan/Latinx community

By Nicole Rudolph-Vallerga

I worked collaboratively with ENVS PhD student Edith Mirabel Gonzalez to develop a project that supports her work with socio-ecological urban gardening techniques and food within the local Oaxacan/Latinx community. For this I created 9 research based watercolor tiles that work to illustrate specific points in Gonzalez’s dissertation. Each image that I created is based on hours of both personal research and in person research conducted with Gonzalez in the field. This included garden visits where I met and interacted with the community of gardeners in order to establish familiarity and trust. We concentrated on scientific images and diagrams that demonstrated interactions between insect herbivores of the C.pepo plant and the plant itself, predators of the herbivores, and gardening practices of the Oaxacan/Latinx community gardeners in the Watsonville and Santa Cruz area. We plan to continue the work in two future endeavors in the form of an illustrated book and a cookbook and are exploring options for funding.

Untitled (sandbags)

By Lowen Hatano

Co-advised with the Center for Creative Ecologies

Untitled (sandbags) is a project that experiments and materializes theoretical and critical frameworks concerning time, place, and performance. By investigating how our bodies respond and react to place Untitled (sandbags) is manifested through rituals that embrace transformation. Untitled (sandbags) advocates for the land as body by amalgamating with forces that transform environments. In other words, Untitled (sandbags) encourages an awareness of the traces of interactions. This ongoing project persistently experiments with the body’s endurance concerning the site specificity of coastal locations.

Through a series of performance iterations, Untitled (sandbags) showcases the bodies’ ability to become a force that transforms environments. By transplacing sediment to another location, Untitled (sandbags) requires the body to care for another and respond to an extension of the body.

What is the sustainability of sandbags–how do burlap sandbags compare to polypropylene sandbags? Why are sandbags utilized for flood control, military bunkers, and architectural designs?

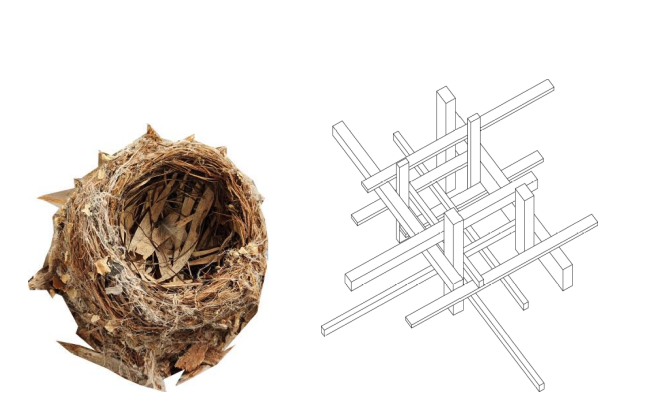

Nest Studies: Designing for the More-than-human

By Isola Tong

Co-advised with the Center for Creative Ecologies

Forest fires in Siberia. Flooding in Banglandesh. The disappearing islands of Tuvalu. Climate change seems to be an inevitable reality even in the most unexpected parts of the world. On the surface it seems like industries that produces huge amounts of Carbon Dioxide are the main villain, but if we take a closer look at the nacre of the problem, it becomes clear that there is something else at work. Since the rise of capitalism in the 16th century and the formation of early capitalists who propelled the violent colonization of peoples in the south, Europeans had become more and more alienated from nature, seeing land, animals and forests not as something to be taken care of, but as a resource to be exploited. This nature-culture divide in the western psyche and the desire to accumulate more power and wealth resulted in the justification of slavery. Human trafficking was a necessary condition to build empires ruled by white men. Methods of othering such as racism, classism, misogyny, queer phobia were necessary to justify the dehumanization of beings that are non-white, non-male, non-Christian and non-human. The intersectional devaluement of life created a condition that allowed the horrors of the current environmental crises.

As I look at the redwood trees close to the balcony of my apartment in Santa Cruz, I noticed Chestnut-backed chickadees (poecile rufescens) nesting on the branches. They oftentimes attempt to peck on the seeds that I sowed in my hanging planters. I eventually decided to feed them with grains from my pantry which they seem to enjoy a lot. My weekly interaction with the birds made me see how entangled I am to them and vice versa. There is no line separating us from them. We are all part of an incomprehensibly large network of agencies that affects each other. And our every action, whether big or small feeds into the system and creates ripples both violent and benign. As a gesture of gratitude for the company and the songs my bird-kin make in the morning I decided to create an architectural intervention, a human-animal architecture, a new building typology that allows for nonhuman agency but aided by human design. Building birdhouses encourages nesting. Providing birds a safe space to inhabit increases their chance for survival, and a possibility for thriving. What does a human and nonhuman design collaboration look like? How do we make worlds together?

Fire Followers

By Dav Bell

Co-advised with the Center for Creative Ecologies

My mother, a retired Southern Californian conservationist and ecological reserve manager, would have been of the mindset we humans messed up. I would be hard-pressed to disagree. However, I am not of the mindset that we don’t have time to repair, reconcile, and heal with the natural world, as we too are natural. In the U.S., humans’ relationship to their environment gets a really bad rap, and it should. The American revolution began with us throwing trash and food into the ocean, and since the people in power today still feel the need to abide by that generation’s logic, we’ve barely begun to think that our actions as a nation have consequences. In California, there are people who have stewarded the land for thousands of years. However, the lay of the land, as well as its needs to be tended to, have long been cast aside, only to be awakened by the one-way white-people know-how, discover it! Similar to how a Bon Appetit editor reveals the health benefits of kale each spring, researchers across the continent are revealing the critical and positive roles humans play in the ecosystem. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who has traveled across the country and read the founded by and insert-name-of-slaveholding/genocidal president signs at each river crossing, followed by a wee bit of information on a didactic suggesting there ‘maybe’ a guide who knew it by another name, a long, long time before.

But here we are.

Plants and mushrooms that were deemed criminal to lock up black and brown folks until proven profitable to white people now decorate magazine covers in every health food market. Millions of Californians ignore unsettling drought conditions while showering their yards with the same water they are upset about being missing from the reservoir when they smash their boats into the corpse-revealing mountainside. Housing costs have gone through the roof (if you are lucky to have a roof), and people are demanding or being forced to build in places they shouldn’t, only to fall victim to the neighbor you would love but only if he was a little less big and scary, fire.

Fire follows the path of least resistance, and the path of least resistance is where humans exist. Capitalism is like fire; it’s fast, easy, and devastating. The privatization of property and poor land management, and the sheer lack of understanding of the California landscape have made fire something we live with out of fear instead of necessity. My recent work shares the story of the fire-following flowers and the importance of fire in an ecosystem. Fire followers are native wildflowers that benefit and rely on wildfires in order to bloom. They can lay dormant in the soil for over 100 years and then sprout up after a fire, guiding in new life after a burn. Some are hidden beneath shrubs, unable to catch the sun’s rays, and once the chaparral is burned finally get their chance to grow. Others, like the fire poppy, only need the smoke and can sprout up miles away from scorched earth. The fire following flowers teach us about resiliency, renewal, and the need to care for and celebrate the land, its history, and the Indigenous people who tended to the very soil that we stand on.