If you have visited a natural history museum you know they are packed full of information and displays filled with specimens. But what is it like behind the scenes in collections of the museum?

Within the collections of a natural history museum lays a wealth of knowledge in the form of specimens rarely seen by the public. What makes these specimens so important is that they are the foundation of the museum’s informational structure. Museums rely on specimens and their associated data to shape educational programs, public displays, scientific research, and to preserve a physical record of the past. The collections staff protect, monitor, and manage the specimens along with their data. As a Webster Fellow, I got a glimpse into the rich history of the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History and the Santa Cruz area reflected within the Museum’s collections.

The Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History (SCMNH) originated with the collection of Laura Hecox in the late 1800s. In 2015, the Museum celebrated its 110th anniversary as an official museum. Since the creation of the museum in 1905, the collection has grown and changed hands with its governance. It now is a private, non-profit organization residing within what was once the Seabright Branch Library building.

My senior internship focuses on the long-term preservation of the bird specimens within the SCMNH’s collection. This is done in five ways: Inventory, Digitalization, Assessment, Cleaning, and Management. The system was developed by discussing what the collections needs are with the collections staff, and reviewing available literature for techniques and ideas on addressing those needs. I inventory the collection to make sure all of the specimens in the museum are in the museum’s records and vice versa. It is important to have an accurate account of what is in the collection.

With the long history of the SCMNH, specimens have been loaned out or damaged over time, and some are missing. During my review of the collection I found a western bluebird that was marked as missing in 1999 on its catalog card. This was likely from the specimen being placed on the wrong shelf but shows how important it is to keep an accurate record.

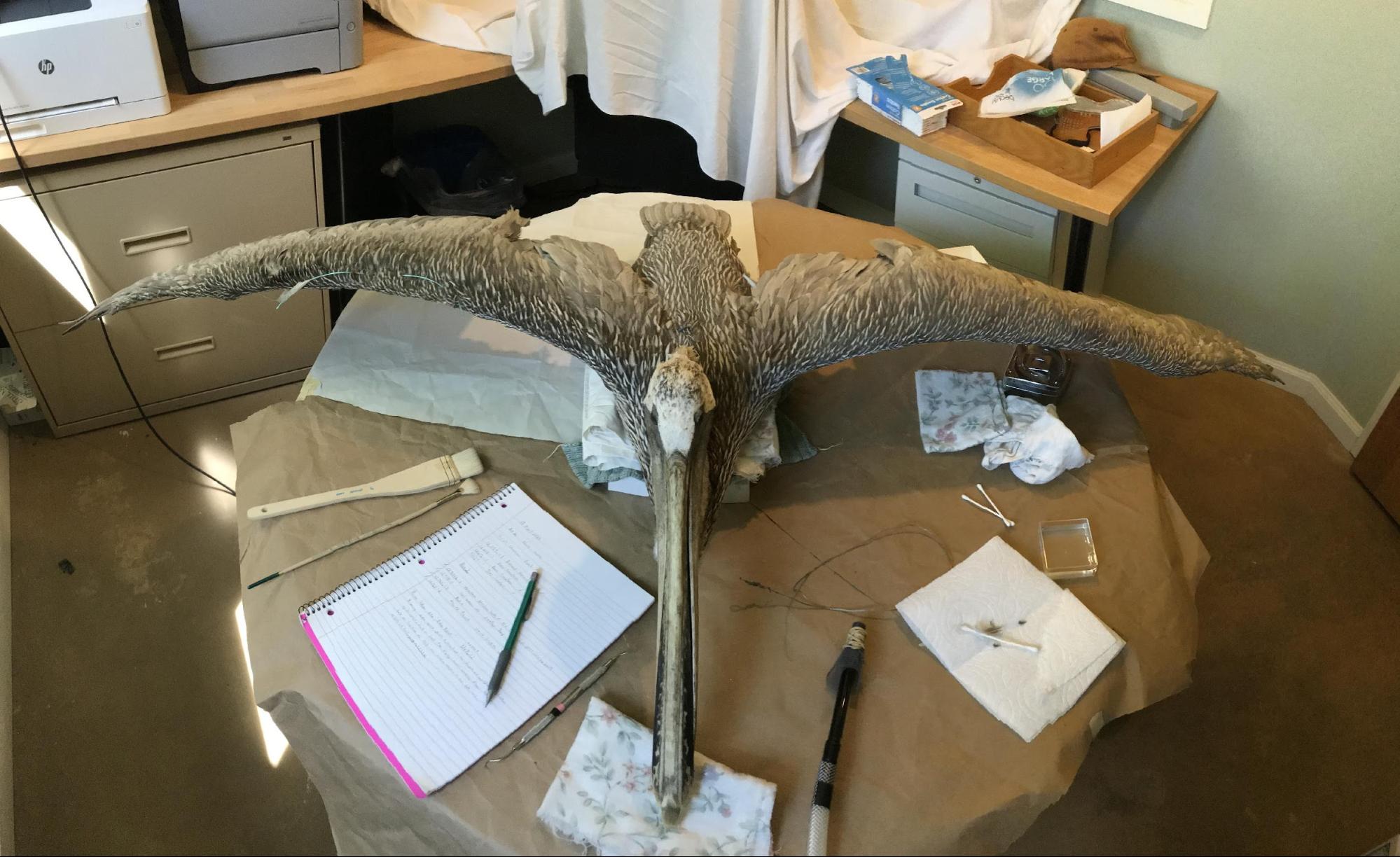

Digitalization involves photographing each specimen and uploading it to an online database, along with a scan

Specimen assessment and

cleaning of a brown pelican.

Photo: B. Johnson

of its catalog card or data card. This is important to preserve a digital copy of the specimen/data, as well as allow digital accessibility of the specimen. Assessment involves reviewing each specimen noting its condition, damage, size, mount, and any other information. The assessment is saved as a hard copy and a digital copy with the specimen. Cleaning is physically removing dust, debris, pests, and doing repairs on each specimen as needed. This extends the life and usefulness of the specimen. All cleaning techniques are noted and saved with the assessment. Management includes finding the best position and material to ensure the specimen won’t be damaged as it or other specimens are moved on the shelf. For example a burrowing owl had been mounted on a piece of wood that was unstable causing damage to the specimen as it would fall over. A solution of using a small box as a frame around the specimen and its storage bag. This allowed the owl to be propped up on the mount as intended preventing it from falling over.

With the experience from this project, I am writing a general guide on museum curation for future SCMNH interns and staff, or those generally interested in museum collections. The guide provides general information, safety, examples, and techniques used while working in and with a collection. This project has opened my eyes more to the importance of natural history museums and piqued my interest as a potential career path.

I would like to thank the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History, The Norris Center for Natural History, and The Helen and Will Webster Foundation for giving me this opportunity to work on the project.