The impetus for this project stems from conversations with family during my time in our hometown of Kimbila, Yucatan, MX, about an hour East of Merida, the state capital. Walking around our hometown my mom or grandma would sometimes stop me in front of a plant and tell me stories about it. Reflecting on this, there was nothing I did to prompt these information sessions, but I always felt excitement to learn what I had missed out on growing up in the United States. In these moments, I felt enthralled by the relationship that my family maintained with their surrounding environment, not simply for the information that it is, but for the larger context in which it is presented to me which I will discuss further in this post.

The impetus for this project stems from conversations with family during my time in our hometown of Kimbila, Yucatan, MX, about an hour East of Merida, the state capital. Walking around our hometown my mom or grandma would sometimes stop me in front of a plant and tell me stories about it. Reflecting on this, there was nothing I did to prompt these information sessions, but I always felt excitement to learn what I had missed out on growing up in the United States. In these moments, I felt enthralled by the relationship that my family maintained with their surrounding environment, not simply for the information that it is, but for the larger context in which it is presented to me which I will discuss further in this post.

What is the project?

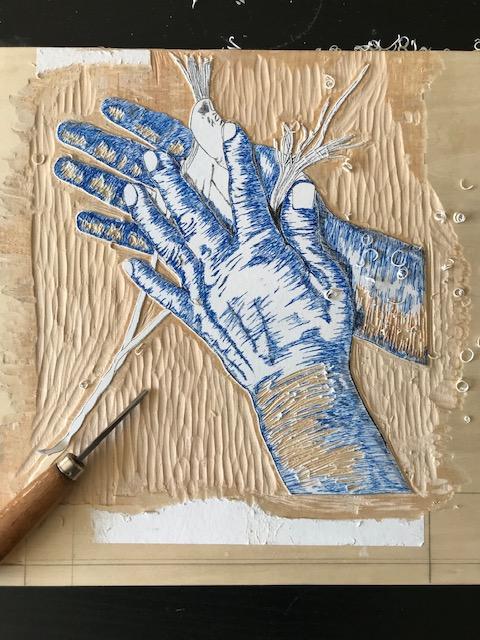

With funding from the Norris Center I produced four block prints that illustrate stories of natural history that the community of Kimbila hold (and likely a larger population of Yucatec Maya people). These stories were told to me through interviews that I conducted over one month in the summer of 2018. The types of information shared with me were vast and varied. For instance, I learned what leaves to use for washing dishes, how to make string out of an agave plant, and medicinal uses of ants that live symbiotically with the bullhorn acacia plant. These prints along with the information passed down to me, will be housed at the Norris Center and available online for reading/viewing.

With funding from the Norris Center I produced four block prints that illustrate stories of natural history that the community of Kimbila hold (and likely a larger population of Yucatec Maya people). These stories were told to me through interviews that I conducted over one month in the summer of 2018. The types of information shared with me were vast and varied. For instance, I learned what leaves to use for washing dishes, how to make string out of an agave plant, and medicinal uses of ants that live symbiotically with the bullhorn acacia plant. These prints along with the information passed down to me, will be housed at the Norris Center and available online for reading/viewing.

The Norris Center’s support of this project is significant. Outside of narratives about the Ancient Maya (which are often highly exoticized (Fedick, 2003)), one will rarely encounter information regarding the way these communities exist in the present day. Outside of acknowledgement, livelihoods in rural Yucatan have been undergoing dramatic changes since the 1970s when tourism centers such as Cancun began to take root in the peninsula (Kemper & Roycen 1979). This integration into the global economy changes daily practices, and goes hand in hand with the loss of Maya knowledge of natural history. This ongoing change in the region sets a precedent to conserve information about current and previous ways of life for the Yucatec Maya that is not based on an exoticized image.

Why does this matter?

What I was most struck by in doing this work, is that natural history in the way we discuss it at an academic institution is a very different reality than how it is practiced in the Kimbila community. For a long time, I did not even recognize the information I was getting from my family as natural history. By creating a place for the Kimbila community’s experience, there is a wider conceptualization of who a naturalist is. In so doing, we redefine the types of experiences that create valid knowledge about the natural world. These are conversations that I hope all centers of natural history are willing to participate in.

What I was most struck by in doing this work, is that natural history in the way we discuss it at an academic institution is a very different reality than how it is practiced in the Kimbila community. For a long time, I did not even recognize the information I was getting from my family as natural history. By creating a place for the Kimbila community’s experience, there is a wider conceptualization of who a naturalist is. In so doing, we redefine the types of experiences that create valid knowledge about the natural world. These are conversations that I hope all centers of natural history are willing to participate in.

My interviews and work are connected to critical questions in fields like social epidemiology and conservation, both of which I hope to interact with in my graduate work. The connections include how scholars can move away from a deficit-based understanding of marginalized communities and instead evaluate the different tradeoffs made by communities that choose to take part in a larger global economy.

Works Cited

Fedick, Scott (2003). “In search of the Maya Forest.” Duke University Press. From In Search of the Rain Forest by Slater, Candace.

Kemper, Robert V., Royce, Anya P. (1979). “Mexican Urbanization Since 1821: A Macro-Historical Approach.” Urban Anthropology. Volume 8, pg 267-289.