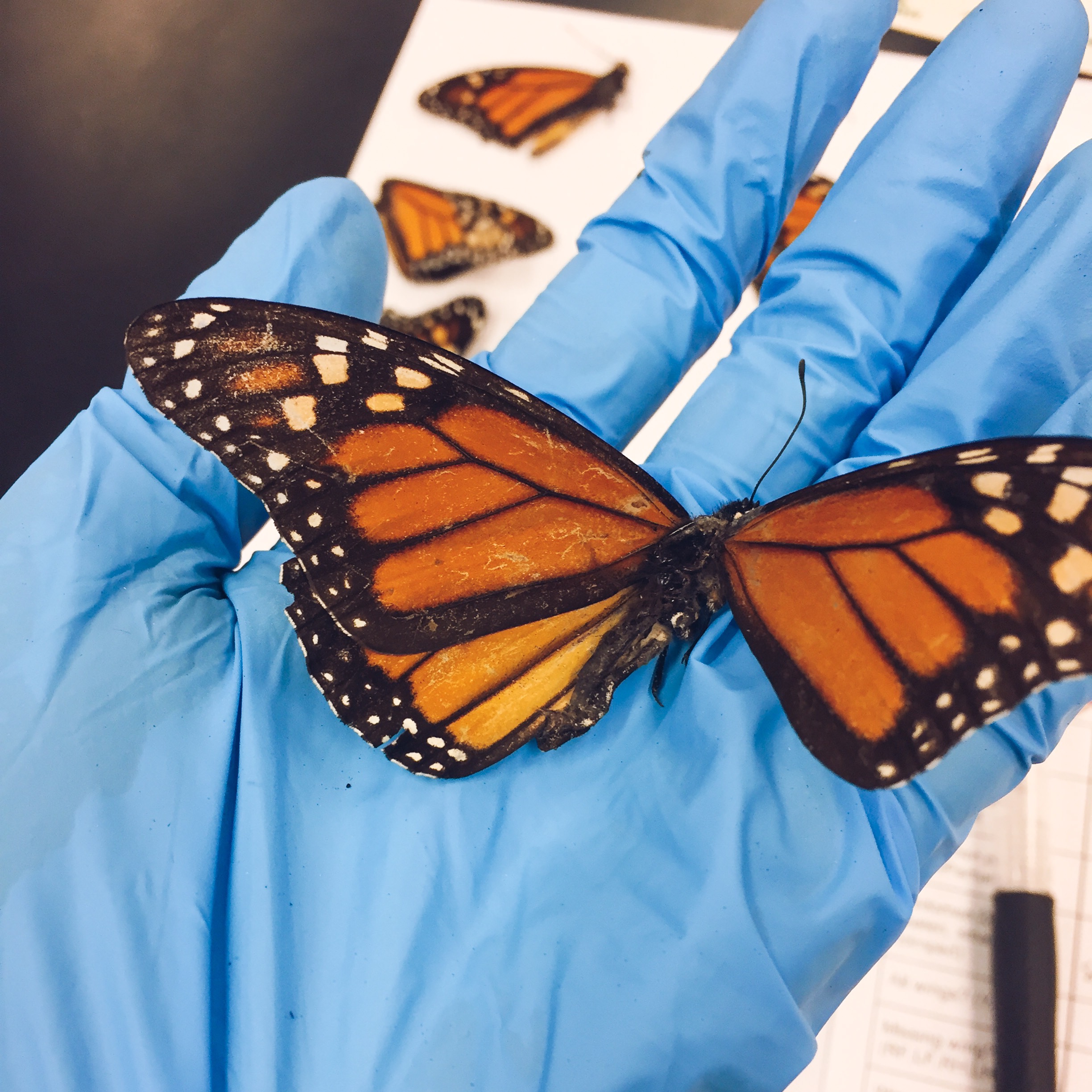

A monarch specimen.

Have you ever been able to go see the large clusters of butterflies at Natural Bridges in the fall or to sit in awe as you watched monarchs flutter around your backyard? Sadly, that experience is now being threatened, as the western monarch overwintering population has declined by an alarming rate in the past several years. According to the Xerces Society, a group that focuses on insect conservation, as of 2015, monarchs had declined approximately 74% since the late 1990s. This magnificent phenomenon, which has captivated millions of people, is at high risk of extinction. This is where my research began - driven to better understand what is happening to the monarchs in an attempt to provide scientific data to understand the decline and hopefully reverse it.

Overwintering monarchs at

Lightouse Field.

Every fall, the adults of three generations of western monarchs take a journey through California, stopping for the winter, or overwintering, along the way. At overwintering sites, monarchs are vulnerable to predation and disturbances from human. In order to understand why monarchs have declined so rapidly, it is important to understand the sources of mortality.

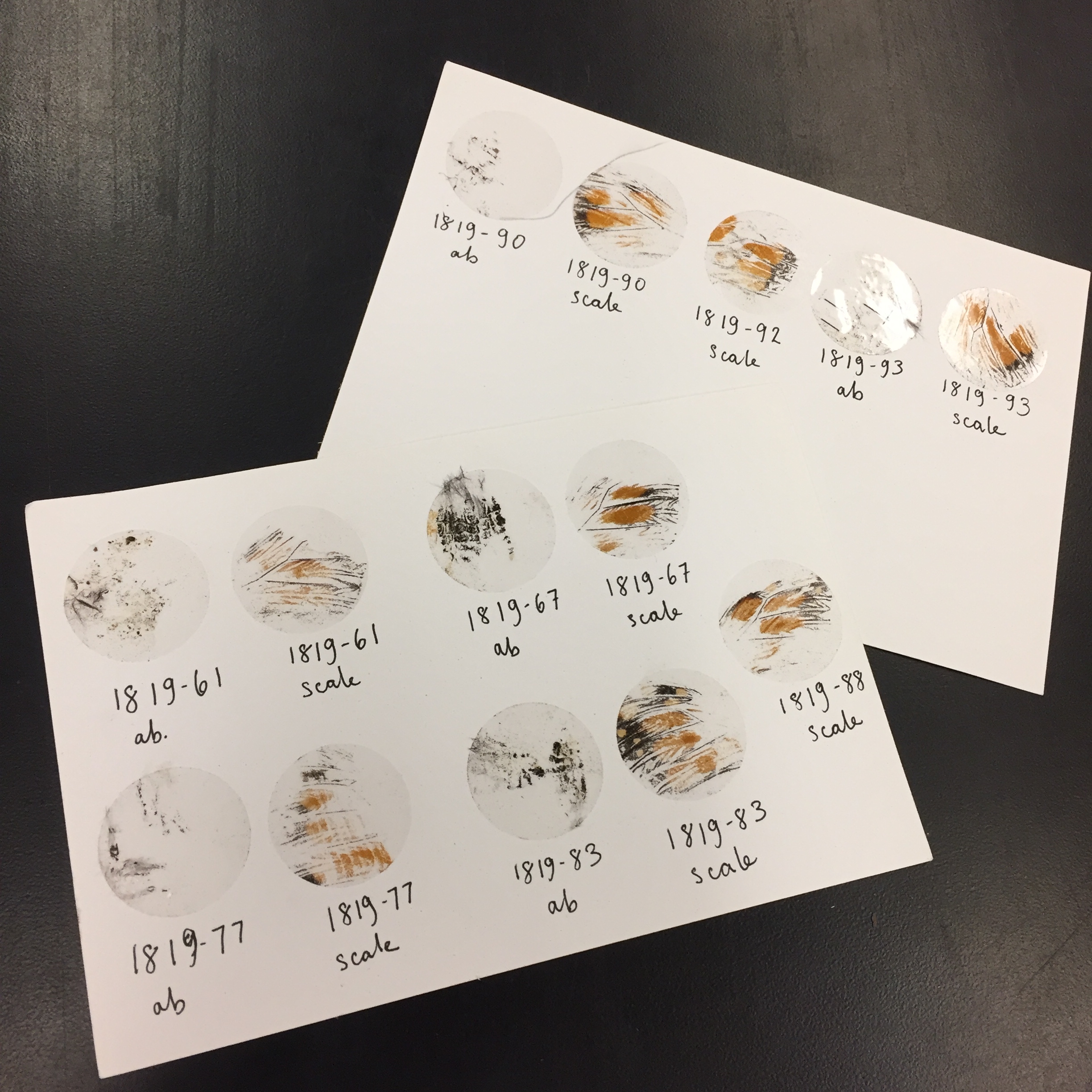

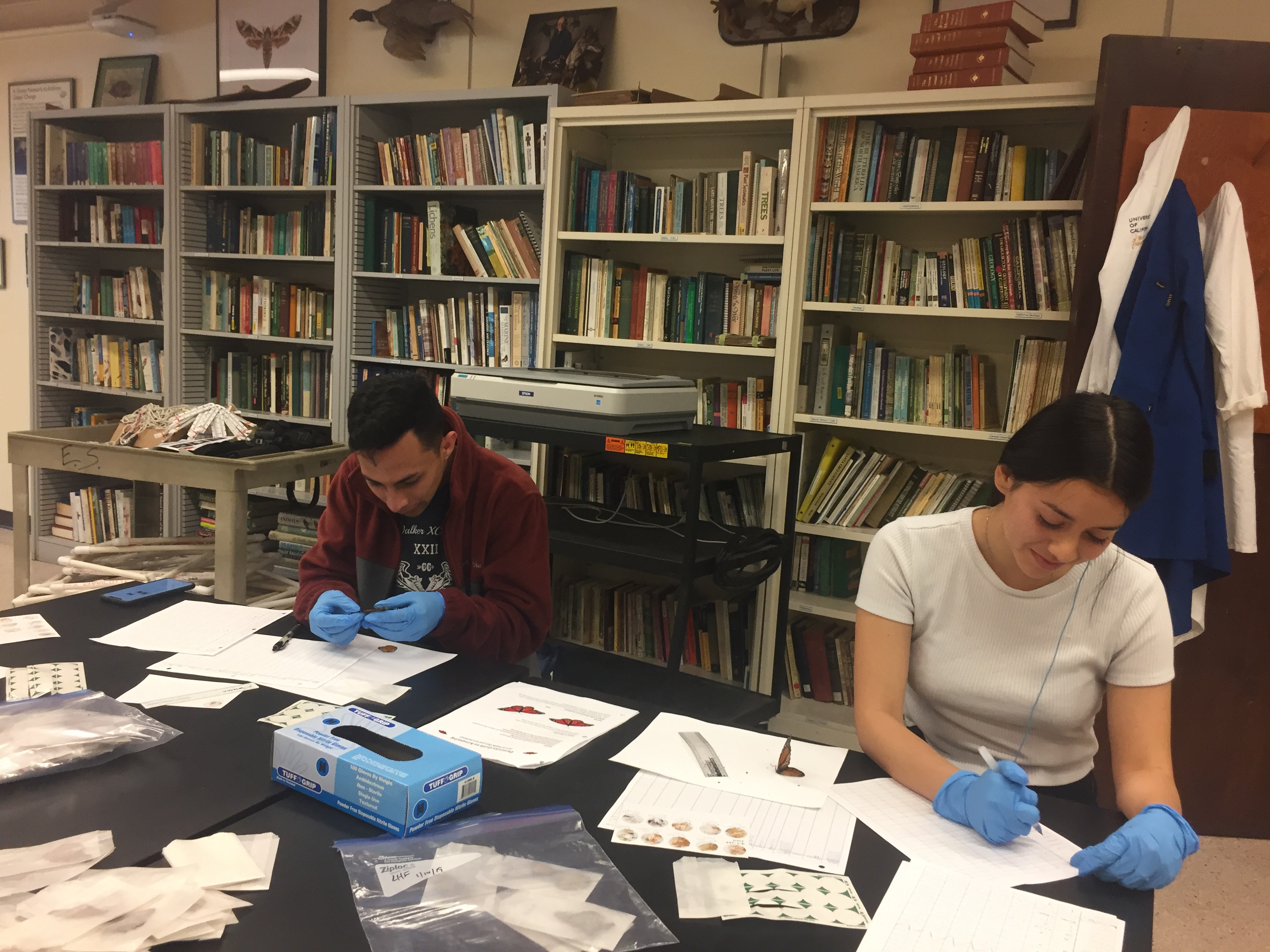

In collaboration with Groundswell Coastal Ecology, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and UC Santa Cruz, I worked to quantify mortality rates and sources at an important local overwintering site. This past winter I walked around Lighthouse Field each week collecting any dead monarchs that I found on the ground or under twigs and leaves. Now, with the help of volunteers, I am examining these monarchs along with those collected in previous years by Groundswell staff and volunteers. We examined physical condition to try to find clues on the cause of death and patterns in mortality rates. Monarch predators include yellow jackets, birds (crows, jays, and others), rodents (rats and exotic eastern grey squirrels). Physical indicators on dead monarchs can suggest what may have killed a monarch, such as tears in the rear wing indicating possible bird predation. In the lab, we record sex, scale loss, wing damage, body intactness, wing size, as well as prevalence of the protozoan parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE). OE, while known to weaken monarchs, has not been formally studied in relation to mortality. We test for OE by pulling scales off the abdomen of a monarch and examining them in a microscope. While originally my interest was focused on OE, unfortunately, the majority of my samples are missing their abdomens.

With historically low overwintering populations this past season, as well as an uncharacteristically early flight from the overwintering site, analysis of this year’s population leaves more questions than answers. The dead specimens collected seem to be in much worse physical condition than previous year’s collections. Although it is difficult to attribute a cause to this phenomena with any certainty, I am left wondering if this year’s population started off in a weak condition due to migratory barriers such as the recent fires in Northern California and/or harsh winter storms.

Our measurements are indirect inferences of predation, not actual observations, given that samples were collected post-mortem and the death was not observed. During the 2017-18 season predation rates were 12.6% of the maximum mortality population count. Of that, yellowjackets stood out as a dominant predator, but other predators were present as well. It is unclear if this predation phenomenon is restricted to my study site because limiting research to one location does not provide a comprehensive picture.

Volunteers conducting monarch

autopsies at the Norris Center.

My research is contributing to ongoing mortality studies on the central California coast and education of the public through outreach via signage and online communications. By collecting data on this year’s mortality rate, researchers and managers can better understand continuing patterns and implement adaptive management strategies. For example, one such strategy I helped implement was to control yellow jackets around the overwintering colony. I hope my work will not only inform management that benefits monarchs but also inspire the public to help to keep this beautiful species flying in abundance.

Thank you to the UCSC Norris Center for helping fund this project in collaboration with Groundswell Ecology, USFWS Coastal Program, the Xerces Society, and California State Parks.